Internalised PDA - the quieter, but equally impactful presentation of PDA that's hard for people to spot

This blog article is also available as an animated video: click here to view it

PDA research & writing has focused on externalised, freely-expressed presentations of PDA.

However, internalised PDA is often completely missed because our meltdowns are concealed and demands tend to be avoided subtly, and we slip below the radar.

We internalisers though are not "less" PDA. Just like an iceberg isn’t smaller than a same-sized lump of ice on dry land: the iceberg merely looks smaller because the majority of its body is hidden from view under the water.

Internalising PDAers’ driving forces are just as strong as those that drive externalising PDAers, and can lead to self-harm, dropping out of school & employment, and even suicidal ideation.

I believe that internalised PDA needs to be brought into the radar.

As we’re so good at concealing our traits, it takes internalisers like me to signpost people to our quieter, less accessible half of the little-explored PDA continent.

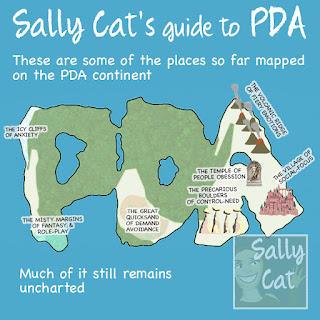

The only PDA maps easily available were drawn by non-PDAers and have sketchy details and guessed content saying things like “here be dragons”. But, as an inhabitant of the PDA continent whose been doing a lot of exploring and getting to know my neighbours, I’ve been putting together a much more detailed and accurate map, which I’m happy to share with you during today’s tour.

So please step this way for your guided tour of our PDA continent, in which we’ll spend most of our time in the part we internalisers inhabit. Your tour will include:

- What PDA actually is

- Internalised meltdowns

- Forms of masking

- Situational (aka "selective") mutism

- 'Spare play’ (children feigning playground sociability)

- Fight versus Fawn, and other adrenaline responses

- How to support internalising PDAers

What PDA actually is

We’ll start our tour by looking at what PDA actually is. As we’ve seen, outside appearance is just the tip of the iceberg for PDA.

Understanding of PDA is still very much in its infancy. There is no definite knowledge about it.

But there are a few core traits that most people, including actual PDAers, agree with.

To understand what these core traits are, it might be helpful to have a fly over of the PDA continent. Here you can see it from space. As you can see, much of the PDA continent is deeply forested. We can’t easily see what lies beneath the forest, but there are clear areas that are easier to make sense of. Let’s have a look:

- The Great Quicksand of Demand Avoidance covers quite a huge area. This sand is extremely sticky. If caught in it, it holds you fast so you’re trapped, and it’s very, very hard to move at all.

- The Icy Cliffs of Anxiety form a fearsome obstacle. To get past them, people must follow a path along a narrow, slippery ledge at the top of a precipice with a drop of a thousand meters onto jagged ice splinters. Howling winds make it even harder to stay balanced. People have been known to totally freeze here, unable to move at all.

- The Precarious Boulders of Control-Need are an unusual geographical feature. The boulders are balanced very precariously on the pillars of rock that support them. It won’t take much at all for them to become dislodged so they crash down onto the ground.

- the Volcanic Ridge of Fiery Emotions are an extremely volatile place! Great big bursts of strong emotion can erupt at any moment without warning.

- The Misty Margins of Fantasy and Role-Play are shrouded in mist, so it’s hard to make anything out clearly. People here might be one thing, or they might be another. They can switch who they are as if by magic.

- The Village of Social-Focus has lots of residents, but there are high walls separating residencies. Even though PDAers are interested in other people, we still have a high need for privacy and personal space

- The Temple of People Obsession isn't visited by all PDAers (we don’t all develop obsessions about people) but many do. These obsessions can be all-consuming and really hard to break out of.

So now we’ve toured the easy-to-spot features of the PDA continent, but we have not yet seen what’s hidden within the deep jungle. Flying overhead won’t give us any clues. We need to get down to the ground level if we want to find out what’s hidden here. This is the realm of internalised PDA.

So, I’m inviting you now to come with me into the dark, uncharted forest. Are you ready?

Welcome to the little-known realm of internalised PDA. Very few outsiders have ever been here. But fear not, I’ll guide you, even though the geography is very hidden.

Masking

When PDAers who generally externalise mask, they are internalising, because masking is totally about concealing our inner emotions and thoughts.

Many people think of masking as an unhealthy thing which autistic people are forced to do by neurotypicals (people with "normal" brains). While this, sadly, does happen, not all masking is like this.

Some masking is actually instinctive. It’s well-known to science that rabbits and other prey animals mask illness and vulnerability so they don’t look like easy targets to predators.

Masking can also be used to help us communicate successfully. If, for example, we’re in a party or maybe a job interview, it’s quite normal to adopt a mask of expressions and mannerisms that we know from experience are likely to go down well. This is not because anyone’s forced us to suppress our natural selves, but because we’re not sure of the “language” the person we’re talking to uses.

Many PDAers identify both with instinctive masking and using masking as a communication tool. We feel confused when autistic people talk about “dropping their masks” because doing that feels neither possible nor desirable.

It’s a confusing area, but I can tell you right now that the masking I carry out nearly always feels jumped on me, and very rarely like something I’ve thought about doing, or had a choice with. It feels natural and automatic.

Internalised meltdowns

Our internalised meltdowns can totally confuse people because they don’t look anything like what people think meltdowns are.

Most people think of meltdowns as very, very obvious things that can’t be missed because meltdowning people are out of control, loud and probably violent.

But meltdowns can be pulled inside – internalised – so they’re not obvious to observers.

Internalised meltdowns are, I think, the defining, key feature of internalised PDA.

So what do they look like from the outside? Well… nowhere near as flashy or as explosive as externalised ones which have no holds barred. Internalised meltdowns have the same amount of discharging, aggressive energy, but it’s choked inside (like a swallowed firework) and can express itself as a barrage of awkward, mean accusations. Or as an irrational, difficult mood where everything’s argued with. We might start punching our own head. Or, even, quietly cut ourself with a knife, or pull our hair out in clumps when no one’s watching.

So, and here’s a big point, while internalised meltdowns might not trouble observers, they do cause huge trouble and pain for the people who experience them. They can cause us to alienate the people closest to us, because we’ve gone into “bitch mode” and said horrible, nasty things for no apparent reason. And they can cause us to subject our own bodies to physical harm.

When I go into meltdown it’s truly horrible. I absolutely hate it. Every second. It’s like a demon has possessed me. I’m completely out of control. I witness myself with shocked horror as I fire a barrage of cold, heartless, mean words at someone I love. I hate myself for saying all these words that I know will hurt them. I cringe inside. But I can’t shut up. I can’t stop myself from saying all these nasty, nasty words that I’ve dredged up to inflict maximum emotional damage. It honestly feels like I’ve been possessed by a devil whose gained access to all my memories and every dirty piece of knowledge that could hurt the person it’s chosen to attack: the beloved person my mouth is spewing spite at. I blame myself for every cruel slur I fire at them. My ego deflates with my shame. How can I be so horrible? What’s wrong with me?

This question, “What’s wrong with me?” plagued my life until I discovered my neurodivergence after decades of trying to figure out why I couldn’t just get along in the world or with other people, even though I’d tried. Not knowing what was “wrong with me” caused constant, major depression, substance abuse and zero self-esteem.

Why did workplaces trigger me to flee within minutes so I couldn’t earn an income to live on? Why couldn’t I will myself to keep my home clean? Why did I avoid all aspects of personal hygiene (for example, every damned stroke of my hair brush) even though I wanted to be well-groomed and clean? Why did I keep getting overwhelming crushes on men so I couldn’t stop thinking about them and drove myself crazy, but when decent people came into my life, I tended to panic and flee as fast from them as I did from jobs. What was wrong with me? Why was I incapable of enjoying the company of anyone, bar a very, very small number of people, and why couldn’t I make new friendships as easily as everyone else seemed to?

I recently watched a TV program where a doctor said that loneliness is as bad for health as smoking fifteen cigarettes a day.

Considerably more than fifteen a day, I thought, if loneliness compels you to chain smoke!

“Don’t be proud,” he said, “just go out there and find companionship.” Umm, well, if it was that easy, I’d not have spent so much of my life depressed and desperately lonely! I can’t just make friends. It’s like I’ve got a force-field of fear and self-doubt preventing me from relaxing with people that I don’t know well.

On top of this, I’ve spent my life saying things and behaving in ways that turned out to have insulted people and/or weirded them out. My sense of humour – which can be very dark – confused them or made them uncomfortable.

I failed to read social signals of “welcome" or “go away”.

Compounding matters even more, I have something called “rejection sensitive dysphoria” (let’s call it RSD) that makes me hyper, hyper sensitive to any imagined rejection, so it feels that every, single person in the world hates me, and this feels awful beyond words.

Now add to this my over-sharing naiveness, and I was an easy target for bullies at school. I was like a fish out of water. And miserable. School was total hell. The other children shunned me and I didn’t know why. But it hurt. Deeply.

As you’ve maybe picked up, there are some pretty dark corners in the internalised realms of the PDA continent!

Spare Play

‘Spare games’ was a term coined by a nine-year-old girl who speech and language therapist Libby Hill once had as a client.

It means skipping about in the school playground so it looks like you’re playing with the other kids. But you’re not really interacting with them at all.

Libby says she’s since met many other PDA and general autistic children who do this.

Our daughter’s SENco witnessed her spare gaming aged 5, and then still doing it last year (she may well still be doing it now)

I spare gamed too. I had energy to play, but no one to play with because I couldn’t connect with my peers. I’d switch into my latest immersive daydream scenario – one involved me living in a wooden hut in a forest with tame fawns – and skip around acting it out.

From things my daughter told me after school, coupled with what the SENco told us, it seems she’d been acting out her own daydream of getting up to outrageous mischief with her classmates. The reality has been that she’s been mute in school and scarce interacted with her classmates at all.

Her teachers and SENco have been supportive and encouraged other kids to invite her to play, but she told us they annoy her and she prefers to be alone.

Libby Hill told me that some of her young, spare gaming clients have said they’ve preferred to play solo, but others had wished they actually could play with their classmates. This was the case for me. I just lacked the ability to bond with them. I hated feeling like a social failing misfit. It was depressing and my self-esteem plummeted.

Now, the important thing I think people need to know about spare play is that many teachers, SENcos and visiting assessors don’t know to look out for it. They see the child in the question appearing to be playing actively with their peers and assume they’re getting along just fine and have no social issues.

The trick is to keep on watching the child. If they’re spare playing, it soon becomes clear that they’re not interacting with their peers at all.

Selective mutism

Let’s now take a peek at situational (aka "selective") mutism.

Selective mutism (which some neurodivergent people prefer to be termed "situational mutism") means being very quiet in some situations, e.g., in school, but not in others. We’ve already seen that my daughter, Millie, is like this. While she has scarce ever spoken in school, she’s loud, lively and talkative at home with us.

I relate to how she feels because selective mutism has majorly impacted me too. I didn’t know it had a technical name until I watched a PDA Summit webinar by Libby Hill a couple of years ago and I realised what I’d thought of as ‘my fear wall’ is selective mutism. It’s so great when I can connect my lived experience to known theories (the wiring of my brain has been an ongoing tangle to unravel!)

Google tells me selective mutism is caused by extreme anxiety, and I can totally attest to this from my personal experience. It’s horrendous! It feels like an impenetrable column of ice has engulfed me so I can’t speak to people even though I want to. No matter how much I’ve wished to speak freely and connect with others, this ‘fear wall’ has been unbreakable. I never chose to have it, and didn’t know how to make it go away.

As an adult, often lonely, I sometimes decided to take positive action and just go out and connect with people. I’d choose people I thought I’d likely be able to relax with, and sit down with them, making all the right moves, but that dratted wall of icy anxiety would spring up to paralyse me. It was a curse!

So, we’ve seen what selective mutism feels like, but what does it look like to observers?

The NHS’s webpage on selective mutism says:

Selective mutism usually starts in early childhood, between age 2 and 4. It's often first noticed when the child starts to interact with people outside their family, such as when they begin nursery or school.

The main warning sign is the marked contrast in the child's ability to engage with different people, characterised by a sudden stillness and frozen facial expression when they're expected to talk to someone who's outside their comfort zone.

This totally fits how it went for Millie. When I started taking her to playgroup when she was a year old, she ignored the other toddlers. She reached past them for toys as if they were invisible. I remember the playgroup organisers filling an inflatable paddling pool up one afternoon and encouraging us parents to strip our little ones down to their nappies and sit them in it. Millie sat there rigidly showing no awareness of the three other toddlers crammed in around her. Her expression and posture was rigid, almost like she was made of stone.

I’d come to suspect my own autism just after Millie’s 2nd birthday when I came across a female autism traits list on Facebook. The trait that most grabbed my attention was masking & social mimicry (we’ll come back to this). I sought and gained my autism diagnosis a bit later that year, and then began to notice signs of autism in Millie. The playgroup organisers hadn’t heard of female pattern or masked autism, and told me that Millie was just shy. She was fine, they said.

But I didn’t think she was “just fine”. She clearly wasn’t happy at all. I could sense her anxiety like a silent car alarm blasting in my brain. She started nursery and was rigidly silent there too. Both the nursery manager and a senior health visitor dismissed my belief that Millie was autistic. The senior health visitor said she knew all about autism and Millie’s notes showed no sign of it at all.

And she’s had this exact same rigid expression in every photo snapped of her in school. From foundation, right up to year 5, her teachers have produced learning journal books and display boards showing Millie and other children going about their activities. The wooden rigidity of Millie’s expression has patently been obvious in in every photo.

Thankfully my GP and the local autism assessment centre had seen the merit of my concerns and Millie gained her own autism diagnosis just after her 4th birthday. This has meant that her school SENcos and teachers have better listened to my concerns about Millie’s veiled anxiety. They have supported her as best they can (as we’ve seen, she’s resisted playing with her classmates even when supported to do so). She’s starting secondary school in September. I really hope she’ll be OK there.

Masking revisited

Something I think it’s worth bearing in mind is that situational/selective mutism creates a type of ‘masking’ because it paralyses us so we can’t freely express ourselves. We can’t smile or swing our arms around to show enthusiasm. We can’t communicate unhappiness either. Or fear. Or anger. Or anything at all. Everything we feel is masked by the ice that’s engulfed us.

Millie has told me that she doesn’t want to stand out as in anyway different from her classmates. She doesn’t want special treatment. She even gets anxious if she scores well in a test. It upsets her. She wants to get average scores.

So we’ve seen two or three types of masking which we PDAers may experience:

- Rabbit-style hiding of vulnerability; which may be the same as...

- Situational/selective mutism (which freezes us so we can’t express any feelings at all)

- Masking that enables us to communicate when we couldn’t have done so otherwise.

Neither of these masking-types are what autistic people are referring to when they talk about "dropping their masks".

I think this really important for people to realise (hence my revisiting the topic).

Internalised PDA: what we’ve seen so far

So what we’ve so far seen in this tour of the internalised part of the PDA continent is:

- Masking

- Internalised meltdowns

- Spare play

- Selective mutism

I should clarify that not all internalising PDAers do all four things. Some might be selectively mute, but have externalised meltdowns. Others might internalise their meltdowns, but talk freely in school and play with their peers. However, every one of these traits causes our feelings, thoughts and desires to be hidden from view. In other words, internalised.

Adrenaline responses

We’ll now have a look at adrenaline responses. Most people are, I think, familiar with the ‘fight/flight/freeze’ trio of adrenaline responses, but there are a few lesser-known ones we’ll be taking a peek at too.

We’ve seen that externalising PDAers don’t filter their meltdowns so they burst out as obvious explosions of stressed emotion. And also we’ve seen that we internalisers swallow meltdowns inside, maybe kind of like throwing a heavy blanket over a grenade to contain its explosion.

The same difference between externalising and internalising holds true for people’s adrenaline responses.

Animals developed adrenaline responses right back in the dawn of time to protect themselves from threats, and we humans inherited these hard-wired protection responses.

PDAers have naturally high anxiety which makes us super-prone to our adrenaline responses being triggered. But the way adrenaline causes us to automatically react may seem peculiar, especially if:

- What we perceive as a threat isn’t obvious to observers (for example, feeling trapped by a demand)

- Our adrenaline reaction is internalised so it comes out, perhaps, as fainting, being eager to please, telling blatant lies or even clowning around.

As I said, most people have heard of the ‘fight/flight/freeze’ trio.

Fight and flight are what’s known as primary defence mechanisms for dealing with threats. Maybe think of a momma bear fighting to protect her cubs, and a deer fleeing from a wolf: natural instinctive reactions to deal with threats.

Freeze is fight or flight put on hold. Think of a rabbit caught in headlights.

A fourth adrenaline response is flop. Flop is a secondary defence mechanism where an animal, or human, becomes immobile, or even faints, after the predator catches them. Although flop can look like freeze, it only happens after the animal’s been cornered so fight and flight are no longer options.

When an animal (or person) freezes like this after being trapped, it’s termed ‘tonic immobility’. If they faint, or play dead like a possum, it’s termed ‘collapsed immobility’.

This could maybe account for selective mutism: we go rigid because we can’t fight or flee.

The flop response is known to be common for people who’ve been sexually abused so they were trapped and couldn’t fight or flee.

A fifth adrenaline response is fawn. When animals do this, it’s termed “submissive behaviour”. Think maybe of a dog bending down submissively so a bigger dog doesn’t attack it. When people fawn, they try to please others at the expense of their own self-care.

The final two adrenaline responses I’m going to talk about are unusual because they’re not known in the animal kingdom. They seem to have developed out of the complexity of pressure and opportunity human society has created. Their ‘F’ names are fib and funster.

OK, so now we come to funster.

The funster adrenaline response isn’t very well-documented, but I think many people listening here today will identify with PDA children flipping into a manic, hysterical clown-mode when they’re with people they don’t feel relaxed with.

When we went out for meals with people Millie didn’t know well, she used to crawl under the table, giggling, and undo their shoelaces. She’d not, though, be able to look them in the eye or sit relaxed where they could see her.

This was her funster mode. I relate to having gone into funster too. It’s a panicked clown state I’ve flipped into when I’ve felt trapped in social interaction situations where I’ve felt major panic about what I’m supposed to say and do. How I am supposed to behave? I think there’s a demand avoidance issue going on too: the demand to behave *correctly* has often tipped me into behaving incorrectly, and my giggling, silly funster response has been a way of dealing with the pressure.

OK, so here we are now at the final adrenaline response with is fib.

An article on an online ADHD website called ADDitude Magazine explains

"With complex and advanced language (not available to our primitive ancestors), we have the ability to verbalize both factual and/or fictitious reasoning instantaneously at point of performance, most notably in times of stress and threat.”

I used to fib like crazy as a child when cornered. My driving emotion was total panic. I’ve witnessed Millie going into fib-mode too and intuitively understood it was anxiety-rooted. I knew she felt cornered. Telling her off for fibbing would have just made her panic more.

So, just like flop, fib is maybe a secondary defence mechanism that people go into if caught and trapped.

PDA Society once told me that many of their enquiry line calls are from parents seeking to understand why their PDA kids lie so much.

My very strong hunch is that it’s because of triggered adrenaline, and, as we’ve seen, we PDAers are especially prone to our adrenaline being triggered.

Thank you for writing this. I'm on a journey of self discovery and your map analogy is so effective. I believe I'm autistic and my son is too, and discovering the PDA profile has been like fitting key into a lock or clicking a final puzzle piece into place. My son has been labeled as potentially having ODD, and my partner jokes that he gets it from me. I try to explain that it's not like that at all. ODD seems to be more about not wanting to do things because someone told you had to do them. What happens with us is different. We can't do things, even when we want to. I also really appreciate the part of the presentation you have on another page where you asked parents to describe their PDA kids in 3 words. My son, at 13,is the funniest person I've ever met. My 3 words for him would be funny, brilliant and compassionate.

ReplyDeleteI think it's entirely possible that ODD is not a valid diagnosis at all and that children who receive this diagnosis are either acting out of trauma or they have Autism with a PDA profile. Even many pediatric specialists seems to lack familiarity with PDA and look at a child presenting with anxiety or "defiant" behavior but who may otherwise be smart and relatively sociable and think "no, this child isn't autistic." They look at the stimming and the sensory issues and say, oh, they just also have a sensory disorder. They look at the avoidance and say, oh, they just also have ADHD. (At worst, I think it's still extremely common for professional educators and others to think, "this child is just bad.") Even among practitioners, there's often a fundamental misunderstanding of ASD and an over-reliance on diagnostic criteria that has failed to represent the experiences we hear from adults who were diagnosed later in life.

DeleteThank you. Thank you. I am crying because I feel like you opened my head and put everything in there out on the screen. I cannot express how validated I feel right now.

ReplyDeleteThank you.❤️😭

Another person has just found the missing puzzle piece! Thank you beyond words!

ReplyDeleteI’m a 23 year old male for the USA, thank you so much for creating this outline! I’ve never once seen someone describe so much of my life in such a condensed form. I started to cry when I read the question, “what’s wrong with me?” I’ve asked that question so many times while chain smoking alone and now I know just how dangerous it is. The fact that I know and want to be clean everyday, but having to pick up that toothbrush or razor gets harder every day that goes by. The fib! Oh how right you are about the advantages of the fib. How difficult it is to stop it from leaving your lips, as though you are hearing the words for the first time, just like the person you’re saying it to. Becoming an observer to the malicious phrases you say to does who you care so deeply for.

ReplyDeleteIf I could I’d like to ask if you’ve looked into isolation periods and then re-emerging as a “new” person. I feel as though I’ve had many moments in my life where I cut everyone off, without them knowing. Then showing up a couple months later to a couple years later as the same goofy person they know but changed. Not sure if that’s just me but I wanted to ask.

Thank you again for helping me find a way to explain to those I love how my brain works.

Regarding the isolation periods--I do the same. I wonder if that is part of the "avoidance". My isolation periods are typically after very large events in my life, and it's almost as if the isolation was (and is, as I go through yet another isolation period post-divorce) us PDAer's utilizing some innate ability to step away, albeit in extremes, from what isn't serving us, or from things that would only further overwhelm us, while we recharge and hopefully reconnect with ourselves (though I'm not sure the latter is always the outcome, or even the outcome for anyone else). I wish there were more studies, but I hope many are on the horizon.

DeleteHello. Thank you for this great feedback. This is the thing, internalised PDA is real, but few people suspect it exists (including ourselves!) To answer your question, I used to be petrified of being alone. I had friends suggest I withdrew when I was in a bad way once, but I couldn't face the idea. I started seeing a counsellor who helped me feel OK with my own company and – as soon as I stopped being scared of solitude – I felt myself as a cocoon that a butterfly was going to emerge from! So, yes, I relate to what you say. It was then that I got in touch with my intuition and allowed to guide me. Thanks to this, I began a healthy relationship wheich I've now been in for about 14 years!

ReplyDeleteHi sally cat, after finding PDA recently, reading your blogs and watching your videos have changed my life. I've spent years stuck in a deep hole with this and finally have an answer. I walked outside today and the world felt sunny. I have hope for my relationships and my future now. Thank you for giving me my quality of life back, I am eternally grateful.

ReplyDeleteOmg I'm crying, this is me. I wish I had figured this out sooner! The selective mutism and the masking as a form of language.

ReplyDeleteThis sounds similar to me because when I get stressed or feel threatened, I tend to speak in a mouse voice.

ReplyDeleteWas doing a search as part of work, to help me support someone else. Kept reading. I feel sick, this is me from cradle to almost in the grave to now. This is going to take some time to process and decide on what if any steps towards diagnosis I take, I don't know if my GP will even take it seriously.

ReplyDeleteSuch a valuable resource. We're all subtly autistic (newly identified) and know our son has PDA, but I felt strangely that I was too but couldn't put my finger on how because it was totally controlled/buried. Innate masking! I'd never heard of it but it's so accurate. Reading about how PDA can also be hidden was very validating.

ReplyDeleteBlown away by this article. I've been searching for something that would explain my daughter's actions/reactions for 14 years. This page has many of her behaviours that have always been so disjointed laid out in a way that is easy to understand. Funster is something I've never heard put into words before but after reading it those behaviours make so much sense. Thank you for helping me understand internalized pda. I can't wait to read the rest of your site.

ReplyDeleteThank you so much for writing this. So much of it rings true for me. I had never thought about PDA because I don't exhibit many of the externalized criteria, but reading this I meet almost all of the internalized. I really appreciate you sharing this and making it so easy to understand. I am beginning to enjoy this process of unraveling myself because I learn something new every day, even if it's something hard to look at.

ReplyDeleteSally Cat, I would like to use your images and content in teacher education. How can I contact you?

ReplyDeleteHi, you can email me at sallycatpda at gmail.com (substitute " at " for @)

DeleteCrying reading this, this explains my childhood and adulthood struggles so well, I never understood how no one could see me and now I do

ReplyDeleteThis article describes my autistic 21 year old son. He is currently in crisis , practically mute, and has admitted he’s depressed but can’t bear to think about why .

ReplyDeleteWe have known he has PDA for 8 years . But internalised fits his profile.

What can I do to help him ?

I'm PDA and mask so heavily that I look extroverted and just quirky. Is "spare play" similar to the autistic version (extends past toddler) of parallel play? Where you're sort of an island but still observing others who are playing around you?

ReplyDeleteI'm so appreciative of you for putting into words what I've struggled to when advocating for my internalizing, high-masking child. Thank you for all the work you do.

ReplyDelete